Drink Driving - Providing a Urine Sample

Drink Driving Urine Samples

Are the police taking the p**s?

Initially, when I was first contacted by my client, he was intending to plead guilty. He was resigned to losing his licence and just wanted me to represent him in court to try and keep the length of ban to a minimum.

As usual, the ‘Advance Disclosure’ was only made available at the first court date.

The Advance Disclosure is a bundle of papers containing all the initial evidence that the police and Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) want to use against you. Many people go to court on the first court date not realising these papers exist.

If you are thinking of pleading guilty it is vitally important that the Advance Disclosure is properly reviewed prior to making any final decision.

The Advance Disclosure is a bundle of papers containing all the initial evidence that the police and Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) want to use against you. Many people go to court on the first court date not realising these papers exist.

In a case like this, the Advance Disclosure will usually contain the following documents:

- The charge sheet and bail sheet

- A case summary (put together by the police for the CPS)

- Witness statements from all relevant witnesses

- The MGDDA document detailing the breath test procedure (even if breath was not taken)

- The MGDDB document detailing the urine procedure

- The Streamlined Forensic Toxicology Report

- A PNC record of any previous convictions

If you were taken to hospital, perhaps following a vehicle accident, the police should have completed a MGDDC document. This 36 page form contains instructions for the officer to follow. There are additional considerations for the officer when a suspect is taken to hospital.

If post driving consumption is being raised, and therefore a back calculation of alcohol is required, the police should also have completed a MGDDD document.

It is important to check that all the above documents are contained in the Advance Disclosure. Indeed, it’s not just a case of checking the documents are there, it’s knowing what to look for and how to stop mistakes.

It is possible to win a case simply by finding an error in the documentation. It therefore makes sense to me that we check these documents prior to any final decision being made to plead guilty. It will usually take 2-4 hours to properly review the Advance Disclosure.

It should also be remembered that the Advance Disclosure is just that; advance disclosure. It is not full disclosure. Believe it or not, you are only entitled to full disclosure of the evidence after you have entered a plea of not guilty. In other words, the Advance Disclosure contains only those documents that the police choose to show you before you enter a plea.

Any documentation that the police do not want to use against you (because it weakens the prosecution) will not be part of the Advance Disclosure. You will only be informed of any evidence in your favour after a plea of not guilty has been entered at court. If you plead guilty, you’ll never get to see it!

In most cases, in my view, there is very little benefit in entering a plea of guilty. The length of any disqualification is not affected by the timing of a guilty plea. By entering a plea of not guilty you have everything to gain, and little to lose.

By knowing what to look for in the MGDDA and MGDDB documents, it is possible to win cases very easily. But a word of warning: don’t believe what these documents say! Any mistakes made by the police may not be obvious from the outset.

Let me give you an example from a recent case of mine.

Are the police taking the p*ss? - Taking a sample of urine

My client was pulled over by the police. He provided a breath specimen at the roadside that was over the limit. Back at the police station he was asked to blow again, this time into a larger, more accurate, breath testing machine. The results were inconclusive and so the officer asked my client for a urine sample. I told my client that the first step was to review the MGDDB document.

The urine procedure, including the involvement of the police officer and the timings of the samples, is detailed in a document known as the MGDDB document. Within this form are 20 - 30 questions the officer must ask before the urine sample is provided. In my client's case, I was able to obtain this prior to the first court hearing and review it with him. I was suspicious. Certain sections of the form indicated to me that several mistakes had been made by the police officer during the procedure.

This article will concentrate on just one error made by the police. Importantly for my client, such an error meant the CPS had no case. Let me explain this error in more detail because it’s a situation that arises in many cases where the police request a urine specimen.

The entry on the MGDDB document stated:

“First specimen obtained and discarded by at 2355 hours. Second specimen obtained, retained and divided at 2357 hours”.

Concerning the second specimen, the MGDDB document went on to state:

“Two identical samples were bottled and labelled correctly before giving [the defendant] the option of choosing his own sample”

On the face of it, it appeared that the police had obtained the first sample and discarded it. Then, within one hour, obtain the second sample and split it into two (one for the officer and one for my client). What's the issue?

My client informed me that the ‘first’ specimen was provided directly into the toilet. Only the ‘second’ specimen was provided to the police in a specimen container. This was then divided, with one part being sent to the lab for analysis.

I my view, the police had not correctly instructed my client how to provide a specimen. The first specimen was not provided (within the legal definition). Therefore the ‘second’ specimen was not, in law, a second specimen and should not have been analysed.

Let me explain.

Section 7(5) RTA 1988 states:

“A specimen of urine shall be provided within one hour of the requirement for its provision being made and after the provision of a previous specimen of urine”.

The police often believe that urinating into the toilet is sufficient (in that it complies with police procedure) - but they're wrong. Consider the following case of Ryder v CPS [2011] which states:

“It is, however, plain to me that the word “provides” involves providing it to someone, and that someone, in the context of the Road Traffic Act 1988, is the police officer making a request for such a specimen”.

The case goes on to state:

“A specimen of urine is in my view not provided at the moment it is excreted. Provision involves the concept of provision to someone. As I have already observed, this is plainly to the requesting officer.”

In was my argument that the specimen alleged to have been provided by my client at 2355 hours was not, in fact, provided. My client was taken to the toilet and was allowed to go, by himself, to the toilet. My client did not urinate into a specimen container (as required by law) and, therefore, no urine was provided to anyone at this time.

The first and only specimen that was obtained by the police was two minutes later - at 2357 hours. This was obtained in the sample container. It is this specimen that should have been obtained and discarded (as the first specimen). Instead, it was this specimen that was retained and divided (as the second specimen).

To make matters worse for the police, it was incorrect and misleading for the police to state in the MGDDB document that my client's 'first' specimen was “obtained and discarded” when it was not, in law, obtained or discarded (it went straight into the toilet!).

The police did not understand the law. The police believed that asking my client to urinate into the toilet was the same as obtaining and discarding the urine. There is an element of logic to this. But often the law is not based on logic!

The correct urine procedure

The correct procedure would have involved the officer collecting, from my client, a sample of his urine in a container. The officer should then have emptied away this first specimen (to get rid of any stored urine). The specimen container is then washed out and my client should have been offered as much water as he could drink. After around 40 minutes (but no longer than one hour), a second specimen is obtained, retained and divided. It is clear from the evidence that this did not happen.

No lawful specimen was obtained from my client. No specimen: no evidence.

Needless to say, my client did not enter a plea of guilty!

Procedural Note: You may have noticed that, according to the police, the ‘two’ specimens were provided just 2 minutes apart. In my view, this did not comply with the law. I have written a separate article on this issue.

Urine Samples Given Two Minutes Apart

The second issue that I identified in my client's case related to the timings of the urine samples.

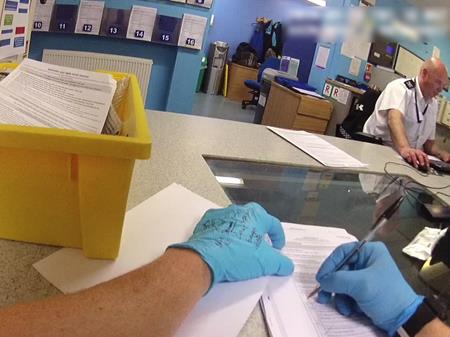

The image below is taken from a section of the MGDDB document provided in my client's case;

You will note that the MGDDB document states that the first specimen was taken at 2355 hours and the second specimen at 2357 hours. This indicates a time difference of 2 minutes. In fact, if you think about it, it could be anything from one minute and one second, to two minutes and 59 seconds. Either way, it's too quick. I'll explain why.

The purpose of the first specimen is to empty the bladder and thereby get rid of old, stored, urine. If my client emptied his bladder at 2355 hours (whilst providing the 'first' sample) it is highly unlikely, if not impossible, for him to have produced enough fresh urine to provide a second specimen within two minutes as indicated on the MGDDB document, especially if water was not consumed after the first specimen.

If a second specimen was provided 2 minutes after the first, it was only because the bladder was not fully emptied when providing the first specimen. In effect, the urine in the second specimen was the same as the urine in the first.

The case that supported, directly, my client’s position was that of Prosser v Dickeson [1982]. This case involved two urine specimens only two minutes apart. The court decided that the urine came from the same bladder content and constituted one specimen, not two. The court said:

The defendant, a motorist who had been arrested and required to provide a laboratory test specimen under section 9(1) of the Road Traffic Act 1972, agreed to provide two specimens of urine within an hour in accordance with a request under section 9(5)(b). He was taken to the lavatory by a police sergeant and at 2.49 a m urinated into a jar, supplying half- to three-quarters of an inch of urine therein when he was told by the sergeant to stop. The urine was discarded under section 9(6) and the jar was washed out. At 2.50 a m the sergeant directed the defendant to resume urinating, which he did. Analysis of that urine showed that it contained not less than 146 milligrammes of alcohol in 100 millilitres. The defendant was charged with driving in contravention of section 6( 1). The justices were of opinion that two specimens of urine had not been provided and that the two portions of urine constituted one and the first specimen; they concluded that the evidence of the analysis was inadmissible and dismissed the information.

It is important to know the the CPS will often quote case-law that purports to strengthen their argument. However, I regularly find that the CPS lawyer in court has not even read those cases in full, but instead has only read the summary contained in the text books or journals. By reading, and understanding, the cases in full, they can often be used by the defence against the prosecution. Let me give you an example.

The case of Ryder v CPS [2011] is often used by the CPS in support of its claim that two samples can be taken close together and that the bladder does not have to be emptied during the first specimen. However, in my opinion, this case is authority for the view that the bladder must be emptied prior to the provision of the second specimen and therefore the second specimen must contain new, freshly created, urine. This case involved a catheter bag which the Judge said, “was like an external bladder… In functional terms the catheter bag was a bladder”.

The court referred to the case of Nugent v Ridley [1987] in which it was stated: “The medical reason why there has to be a previous specimen of urine is well known. It is to ensure that the sample ultimately sent for analysis is a fresh specimen and properly reflects the bodily condition of the person from whom it is taken”.