Failing to give a sample of breath

My client was awoken by a police officer tapping on the driver’s side window of his white Ford Transit van. The police had received reports that a badly damaged vehicle had come to a stop at the side of the road. There were concerns for the driver’s welfare.

After establishing that my client was uninjured, the officer then claimed to have smelt alcohol. He required my client to provide a road side breath sample. The result was 89 microgrammes of alcohol in 100 millilitres of breath, which is over twice the legal limit.

Assuming the road side breath sample was accurate, it was clear then that my client was in charge of a motor vehicle whilst over the prescribed limit. An offence which could result in a 12 month disqualification.

My client was immediately arrested, placed in handcuffs and taken to the local police station.

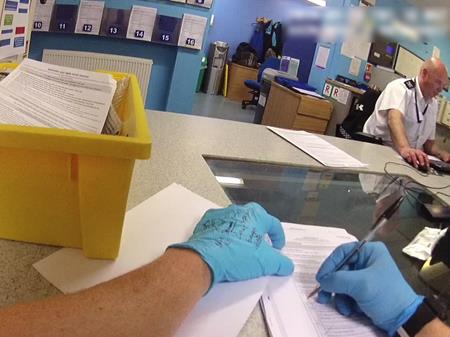

At the police station he was required to provide two specimens of breath on the evidentia breath testing machine. He failed to do so. He was subsequently charged with failing to provide a specimen of breath – vehicle driver, contrary to 7(6) Road Traffic Act 1988.

The CPS’s case

The defendant was driving his Ford Transit van when he was involved in a single vehicle collision. A breath test at the road side confirmed he was over the prescribed limit (89?g%). The van was so badly damaged it could not be driven and so came to a stop at the side of the road. My client, realising he was over the limit, refused to provide a specimen at the police station. He was charged with failing to provide as the vehicle driver.

The CPS clearly thought this was an open and shut case. It was my job to prove otherwise.

STAGE ONE: Evidence that my client was the driver

There are two types of fail to provide offence. The first is where you refuse to provide a sample having been suspected of driving a vehicle. This is the offence my client had been charged with. It can, in the most serious cases, result in a 12 week prison sentence. It carries a mandatory disqualification.

The second type of fail to provide offence is where you refuse a breath sample having been suspected of being in charge of a motor vehicle. This carries a discretionary disqualification (or 10 penalty points).

The commission of a fail to provide offence is not determined by whether an individual drove or was in charge of a vehicle, it is his refusal to provide a specimen. Whether he was driving or not is only relevant in sentencing. Note the difference in the sentencing guidelines:

Fail to provide – vehicle driver

Fail to provide – in charge of a vehicle

The first question is whether or not the prosecution had to prove that my client was driving the vehicle before the court can sentence him as the vehicle driver. The court in Crampsie v DPP [1992] stated, in no uncertain terms, that:

“It was for the prosecution to show the the defendant had been driving or attempting to drive and, if the justices were not satisfied that the prosecution had not done so, the appropriate sanction was a discretionary, not a mandatory, disqualification.”

Following Crampsie, if the prosecution could not establish, as a matter of fact, that my client had been the driver of the vehicle, then the court could not sentence him as one. I put the CPS to proof on this point. They didn’t have the evidence. The disqualification was no longer mandatory but my client was at risk of receiving 10 points (note the guidelines above).

STAGE TWO – Special reasons not to impose 10 points

Special reasons’ is not strictly a defence (as it involves having to enter a guilty plea) but is an extenuating or mitigating circumstance which, if argued successfully, can result in the motorist avoiding a ban.

In the case of McCormick v Hitchins, the court found special reasons not to endorse the defendant’s licence with the obligatory 10 penalty points. These were only applicable if the defence could establish that the defendant:

- Had no intention of driving the vehicle, and

- Could not have been a danger on the road

You may be thinking that these points clearly apply to my client. After all, how could he have any intention of driving when the vehicle was so badly damaged that it could not be driven? Equally, if he could not drive the vehicle, how could he be a danger on the road? Unfortunately it wasn’t that simple. The danger was that the court would refer to it and disregard the damage to the vehicle.

Remember, my only hope in satisfying points (1) and (2) above is that there was damage to the vehicle that would prevent my client from driving it. Disregard this damage and my client could easily have driven the vehicle!

To get around this issue I looked into the purpose of section 5(3). The purpose, it would seem, is to prevent a driver from relying on the defence that there was no likelihood of him driving the vehicle as a result of it being damaged, when he was the person who damaged it in the first place (probably because he was intoxicated)!

However, if the CPS cannot prove that my client was the driver of the vehicle and, as such, cannot prove that he caused the damage to the vehicle, the court should not, in my view, be able to disregard the damage to that vehicle.

The court agreed with this approach and found special reasons not to impose the obligatory 10 penalty points. My client was charged with an offence that could have resulted in him being put behind bars.

Instead, he just was given a small fine.