Incorrectly Completed MGDDA and MGDDB Documents

When I obtained the Advance Disclosure at the first court hearing I immediately became concerned that the police had failed to complete the relevant MGDDA and MGDDB documents correctly. I have copied below the actual sections from the documentation to illustrate the mistakes made by the police.

1. Incorrect Breath Specimen Requirement

The MGDDA document, section A10, indicated that the ‘statutory warning’ was provided to my client. This was disputed by my client. As a general rule it is important not to accept as accurate anything you are not sure about. In other words, to dispute everything. If you dispute it, the CPS has to prove it. If you do not dispute it, it is assumed correct! Note the wording of the breath requirement below, including the ‘statutory warning’.

My client stated to me that he was not given this requirement. He was simply informed that he must blow into the device. It should be noted that a ‘direction’ to blow is not the same as a ‘request’ to blow. You do not have to provide a specimen of breath if you do not want to. It is optional. The police should have explained what would happen if my client refused to provide a specimen prior to asking for his agreement to provide. This did not happen. I therefore made this an issue in the case, meaning the CPS would have to prove the procedure, requirement and warning was given correctly by the officer.

Section 7(7) of the Road Traffic Act 1988 states:

If my client had accepted that this warning was provided to him, he would, in effect, be helping the police to convict him (because the police would not then have to prove this aspect of the offence). However, my client stated that this warning was not provided and so I raised this as an issue in the case. Once this point was raised as an issue it would then be for the CPS to prove it was given. This is an important strategic step. The CPS would need all relevant police officers to attend court at a trial in order to give evidence and be cross-examined. If the police fail to attend court (you’d be surprised how often police fail to attend court) then the CPS would not be able to prove the statutory warning was given.

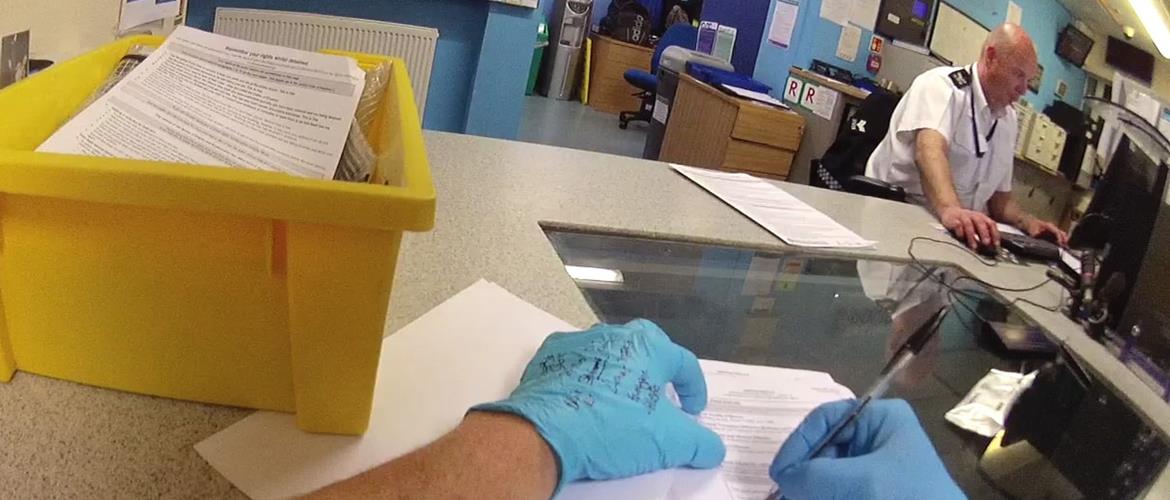

From a strategic point of view, I would also usually request access to the CCTV taken from the breath test room. If the police fail to keep the CCTV (and often they do) then it may be possible to have the case thrown out of court for what is known as an abuse of process. Even if the CCTV is provided it may show that the breath test procedure was not completed correctly.

2. The MGDDA document is not an exhibit

The CPS tried to prove the accuracy of the breath test procedure by exhibiting the MGDDA document into evidence. This case also involved a urine procedure and a separate MGDDB document is used by the police to detail this procedure. The CPS also wanted to use this document as an exhibit. Note the section below taken from the Advance Disclosure documentation I obtained from the CPS:

It was clear to me that the police and / or the CPS did not know what it was doing. Firstly, there was no exhibit reference numbers. Secondly, the MGDDA and B documents cannot legally be exhibits! Note the section below that I have taken from the guidance notes issues to CPS lawyers:

The first paragraph reminds the CPS lawyer to try and get an admission from you. If you admit to something the CPS does not have to prove it! In my view, never admit to anything. You’d be amazed at the mistakes that can be made by the police. Read the second paragraph. Then read it again. It’s important. Most CPS lawyers don’t seem to realise that the MGDDA document (or the MGDDB/C/D) is inadmissible hearsay. That’s correct – inadmissible hearsay. In other words, it cannot be used in evidence. But if you agree the MGDDA in an admission, then it can. General rule – don’t agree!

As far as the exhibit issue is concerned, note also the second paragraph. It states: “If the officer who filled out the form were in the witness box he could not produce the form in chief as an exhibit”. In other words, the MGDDA document is not an exhibit – whether or not the person completing it is in court!

Even if the officer writes a witness statement referring to the MGDDA document as an exhibit, it still cannot be used as an exhibit! The only way the content of the MGDDA document can be used in written evidence is if the content is incorporated into a witness statement. In other words, the witness statement from the officer should contain all the information on the MGDDA document.

If you have been charged with drink driving, check your MGDDA form and witness statement. I bet that the statement from the officer (even if you have one!) does not contain the information from the MGDDA document.

A quick word of warning. Use a solicitor that knows what they are doing. You do not want to rush off to the CPS and point out its mistakes or ask for a properly completed witness statement prior to the trial date. Remember, they have to prove the case against you. If they have not got the evidence, they have not got a conviction. I recently represented a different client on a drink driving charge. I explained to the CPS solicitor at trial that she could not use the MGDDA or printout in evidence. She did not believe me and thought I was joking. She had intended to simply hand over the documents to the Magistrates to read. She insisted they were exhibits and could therefore be exhibited into evidence. After showing her the legal guidance on the CPS website the penny finally dropped. “Oh” she said, “I can’t believe I’ve be using these forms as exhibits for 5 years and no one has ever told me I can’t”. Amazing, but true.

If you have been charged with drink driving and do not remember a MGDDA form being completed with you, the police may have breached the procedure. There are some 20-30 questions that you should have been asked before the police go on to warn you that you do not have to give a breath specimen at all. The police should inform you of what happens if you fail to give such a specimen (known as the statutory warning). Quite simply, if the police failed to warn you of what happens if you fail to provide a specimen then you should not be convicted, even if you went on to provide a specimen.

3. Incorrect ‘Statutory Option’

The MGDDA document, section A20, indicated that the ‘statutory option’ was provided to my client. This is an additional requirement placed upon the police to inform the motorist of their right to replace the breath specimen with blood or urine. Note the actual section below.

The MGDDA document indicated that the statutory option was provided to my client. This was disputed by my client. The officer only informed my client that he had the option to provide a blood specimen. You may think this makes no difference, but it does. In law, even changing wording slightly can result in prosecutions failing. Any motorist, when being given a statutory option, must be informed of their right to replace the breath reading with one of blood or urine.

In my experience, the police will always want you to provide a blood specimen rather than urine. For this reason, the police officer may have simply informed you of your ‘right’ to give a blood test. Again, this is incorrect.

MGDDA Video

4. This was not a “requirement” case

In my client’s case, the MGDDB document, in section B22, stated that this case involved a “requirement” to provide blood or urine. This was incorrect. This was evidence to me of a mistake made by the police and illustrated that the officer did not understand the MGDDA and B procedure fully. Let me explain.

There are only a two situations where a blood specimen may be requested by the police. Firstly, when the ‘statutory option’ has been provided (correctly) and the officer goes on the select blood as the specimen (rather than urine). Secondly, when the police officer is allowed to make a “requirement” that a blood (or urine) specimen be provided, for one of the reasons under section 7(3) RTA 1988. See below.

Section 7(a) applies when there is a medical reason for not supplying a breath specimen, such as asthma.

Section 7(3)(b) and (bb) applies when there is a problem with the availability or accuracy of the breath test machine.

[Note. The remainder of section 7(3) goes on to deal with situations where drugs are detected. This is outside the scope of this article and so I have not included the sections.]

In my client’s case, the MGDDB document was not completed correctly by the police. My explanation here becomes a little more complicated so bear with me. You’ll see where I’m

going. You’ll also see the additional mistakes made by the police. Note the relevant section taken from my client’s actual MGDDB document below.

The circling of the wording was on the document when it was received by me, so I assume is was made by the officer completing the document. It is normal for the police to circle the sections that they believe are relevant. You will note that the officer in this case has clearly indicated that section B22(b) was the relevant section. Totally wrong.

Firstly, the officer is stating that the specimen was “NOT” provided. In fact the specimen was provided because my client was charged with excess alcohol (following the analysis

of his urine specimen). Secondly, the officer refers, in section B22(b)(i), to a “Requirement case”. In other words, according to this section of the MGDDB document, a blood or urine specimen had been ‘required’ by the officer. As there was no evidence of a medical problem (as to why breath could not be taken), the only situation where a “requirement” would be made is because of a problem with the breath test machine. However, there was no problem with the machine in my client’s case. As we already know, my client elected to replace his breath specimen (with blood or urine) because of the ‘statutory option’ (not because the officer required it).

5. This was not a fail to provide case

Section B22(b)(i) clearly indicates that my client failed to provide a specimen “without reasonable excuse”. Incorrect. Failing to provide a specimen without reasonable excuse is a separate offence and only applies where the motorist has failed or refused to provide a specimen. This was not relevant in my client’s case because he did provide a specimen. Note that the section informs the officer to charge with the offence of “failure to provide”.

This is clearly wrong. My client did provide a specimen and he was not charged with failure to provide.

Section B22(b)(i) directs the officer to “go to MGDD/A (A23)”. If you look at this section (below) you will see that the officer has indicated my client should be bailed or released without charge. However, according to section B22(b)(i) my client has failed to provide and should therefore be charged. I would therefore expect section A23(a)(i) to have been completed, but it was not.

6. Consent to urine or blood?

The MGDDB document, section B18, states that the officer has decided the specimen shall be of urine. It also states that my client consented. See below.

However, the officer had previously decided the specimen should be of blood. See section B14 of the MGDDB document below.

7. Did the officer forget about the involvement of the nurse?

The real reason why urine was taken was following the nurse’s opinion that, for medical reasons, blood could not be obtained. In this situation, the officer should have completed section B19 of the MGDDB document, but he did not. See the actual section below.

In addition, the officer did not confirm that my client was asked for his consent. The section was left completely blank.

Remember that the CPS must prove a case ‘beyond reasonable doubt’. In other words, if there is a reasonable doubt as to the evidence against you, you must be acquitted. Imagine if you were one of the magistrates deciding my client’s case. What would you decide?

Note that there were other major problems for the police and CPS with this case. I have written about them separately as they are important issues in their own right. One concerns the legal meaning of ‘provision’ of a urine specimen. Another relates to the lawfulness of urine specimens being taken a few minutes apart. Please refer to my website for more details or contact me by email and I will be pleased to email you a copy.

All in all, this case was an example of a total cock-up by the police, and, in my view, a further cock-up by the CPS for even prosecuting it! I hope this case illustrates to you the importance of properly checking the evidence against you. But remember, you need to use a solicitor that specialises in drink driving cases. If you would like any further information please do not hesitate to contact us.