Unlawful Request for Urine

How we avoided a driving ban

You remain innocent until the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) can prove the case against you. As strange as it sounds, simply drinking alcohol and driving doesn’t necessarily make you guilty of an offence, even if the police have charged you. Many people believe they are guilty before they have even seen the evidence against them.

The procedure involved in a drink driving offence is complicated and time-consuming. Traffic officers in particular seem to be developing a ‘target-driven’ culture - focusing on meeting arrest quotas, ‘ticking-boxes’ and chasing monthly performance figures. I frequently win cases as a direct result of the police making silly mistakes whilst wanting to ‘process’ people as fast as possible.

The aim of this series of case studies is to give you an insight into how I effectively challenge drink driving offences throughout England and Wales. These are real cases, involving real people.

My client's drink driving urine case

At first sight it looked as if the prosecution case was faultless. My client was arrested for providing a positive roadside breath test. At the police station she agreed to provide two specimens of breath for analysis.

However, during her second sample the breath test machine aborted the test due to the detection of ‘mouth alcohol’.

The image below shows the part of the MGDDA form where the officer records the two evidential breath readings.

The officer then asked my client to provide a specimen of blood or urine. By law, the officer is entitled to choose. In this instance, the officer required a blood sample.

Procedural Note: Any individual who is requested to provide a blood sample should be asked whether any medical reasons exist as to why he/she should not provide.

The taking of blood or urine is detailed in a separate form, known as the MGDDB form. My client consented and agreed to provide a specimen of blood for analysis.

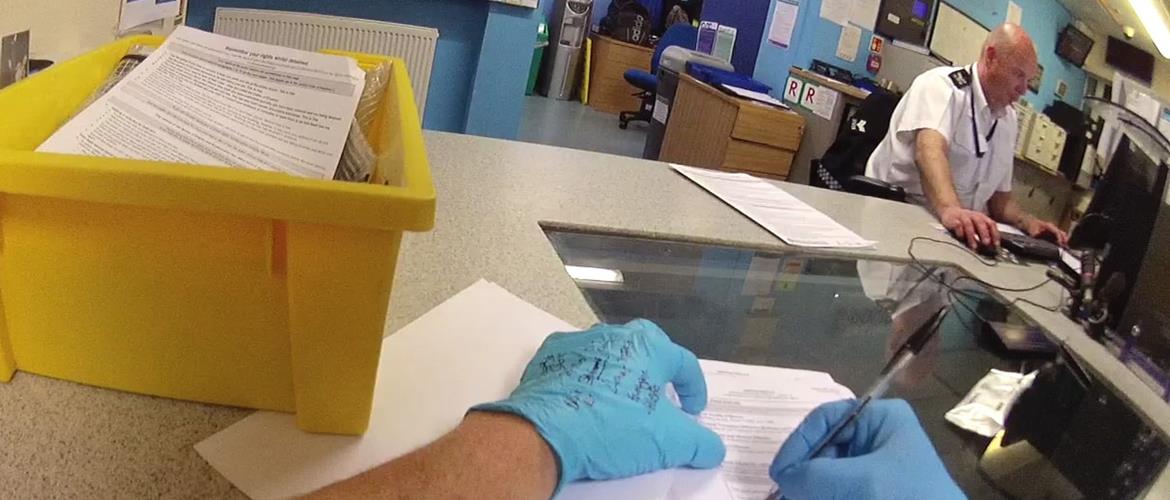

The police station doctor then attempted to take a sample of blood from my client. The MGDDB form below, completed by the officer, states that a sample could not be obtained.

The officer then made a request for a specimen of urine. My client provided a urine specimen and was charged on the basis of the urine reading (188 milligrammes of alcohol in 100 millilitres of urine). As she had a previous conviction within 10 years, she was facing a minimum 3 year disqualification.

Whilst reviewing the officer’s witness statement I realised that something wasn’t right. Please find below the crucial section of this statement.

Hold on a minute... The officer said that the doctor was “unable to obtain a sufficient [blood] specimen”. Remember his note in the MGDDB booklet (above)? He stated that a blood sample was “not obtained”. It doesn’t take a doctor to know whether a sample was obtained or not. You either gave a blood sample, or you didn’t!

I swiftly wrote to the police to request a copy of my client’s custody record.

Fact: A custody record is one of the most important documents required to be maintained by law. It should provide an accurate and contemporaneous record of a person’s detention.

Below is part of the record giving the missing information.

Bingo! The information I was looking for. My client had in fact provided 1.5ml of blood. The officer

then decided that this was insufficient for the purposes of blood alcohol analysis and discarded it. In other words, he didn’t think enough blood had been taken, so he threw it in the bin!

The next issue I examined was whether 1.5ml of blood is sufficient for laboratory analysis. To obtain this information I instructed an independent expert witness.

Note: An expert witness is a person with specialist knowledge or skill in a particular field. Their opinion can be relied upon in legal proceedings.

The expert’s conclusion is detailed below.

I served the expert report on the CPS. If the CPS does not oppose the report, within a short time period, it is deemed agreed. Unsurprisingly the CPS failed to respond (probably due to administration problems) and the report could simply be read out at trial. There was no need for our expert to attend at court and this saved on costs for our client.

I was also able to strengthen my argument and make our defence as tight as possible with the use of case law. One case in particular, namely, Poole v Lockhart, summarised my legal argument perfectly.

The present case can be seen to raise a very short point...the officer asked for a specimen; he received one; he could have used it as the basis of a prosecution. That was the end of the matter. No request made thereafter could lead to the production of a sample admissible against the motorist in a prosecution, for otherwise the prosecution would be able to obtain two samples in respect of the same allegation

Trial

We went to trial and the court returned a verdict of NOT GUILTY - concluding that the officer’s request for a urine sample was unlawful. We were also awarded costs.

By obtaining all pieces of evidence against my client I was able to identify crucial procedural issues and present a convincing legal argument.

The current case raises the crucial question; if a sample of blood was taken from you, how many attempts were there? If during any of the previous attempts the medical practitioner obtained a sample (even if only a small amount), any sample taken thereafter could be unlawful (whether it is blood or urine).